Updated Analysis of Hammond-Hopkins Reports

Assessing progress to address faculty gender and racial inequities (Fall 2024)

At the April 2024 faculty meeting, Provost Cynthia Barnhart gave an update on MIT’s response to landmark reports that uncovered how gender and racial inequities impact faculty: the 1999 Study on the Status of Women Faculty in Science at MIT and companion studies led by faculty in the other schools, as well as the 2010 Report on the Initiative for Faculty Race and Diversity.

This webpage provides an overview of the original reports’ findings, details the updated analysis, and lays out an initial response plan. Provost Barnhart also shared this information in a letter to MIT faculty and instructors in August 2024.

What the original reports found

By seeking out clear data and sharing it with fearless transparency, the authors of the 1999 and 2010 reports shone a light on how faculty members from underrepresented groups, including women, experienced MIT. The studies are exhaustive and compelling, a mix of stark findings and resolute calls for data-informed action.

A few key takeaways:

- During the drafting of the 1999 report, the percentage of women faculty in the School of Science hovered around 8% and had not changed significantly for “at least 10 and probably 20 years.” The report also highlighted numerical data showing significant discrepancies in the treatment of male and female faculty across several dimensions, including salary and space.

- The 2010 study found that compared with white faculty, a disproportionate number of faculty who are members of underrepresented racial ethnic groups left the Institute without promotion, and that faculty from underrepresented groups were half as likely to be promoted to assistant professor and associate professor levels.

Assessing where MIT has and hasn’t made progress

In 2023, a working group of faculty leaders and Institutional Research (IR) staff began to assess progress on the reports. The working group members included: Provost Barnhart, Faculty Chair Mary Fuller, former interim Institute Community Equity Officer (ICEO) Dan Hastings, and Associate Faculty Chair Elly Nedivi.

While this analysis points to a number of persistent challenges, on the whole the results are encouraging.

Here are some headlines from the new findings.

Composition/recruitment

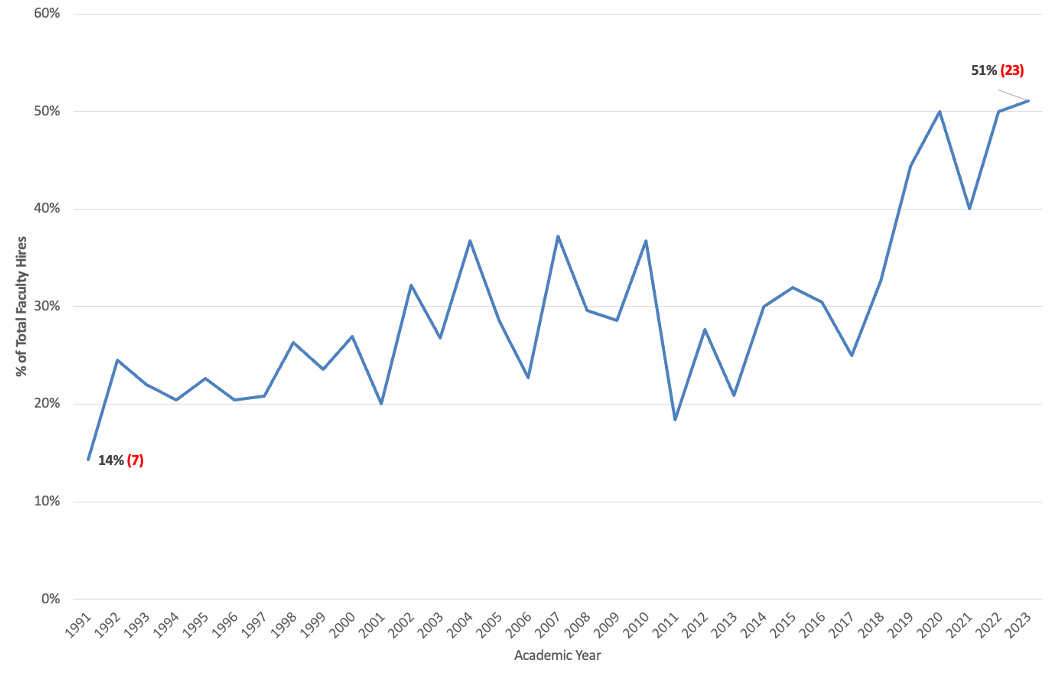

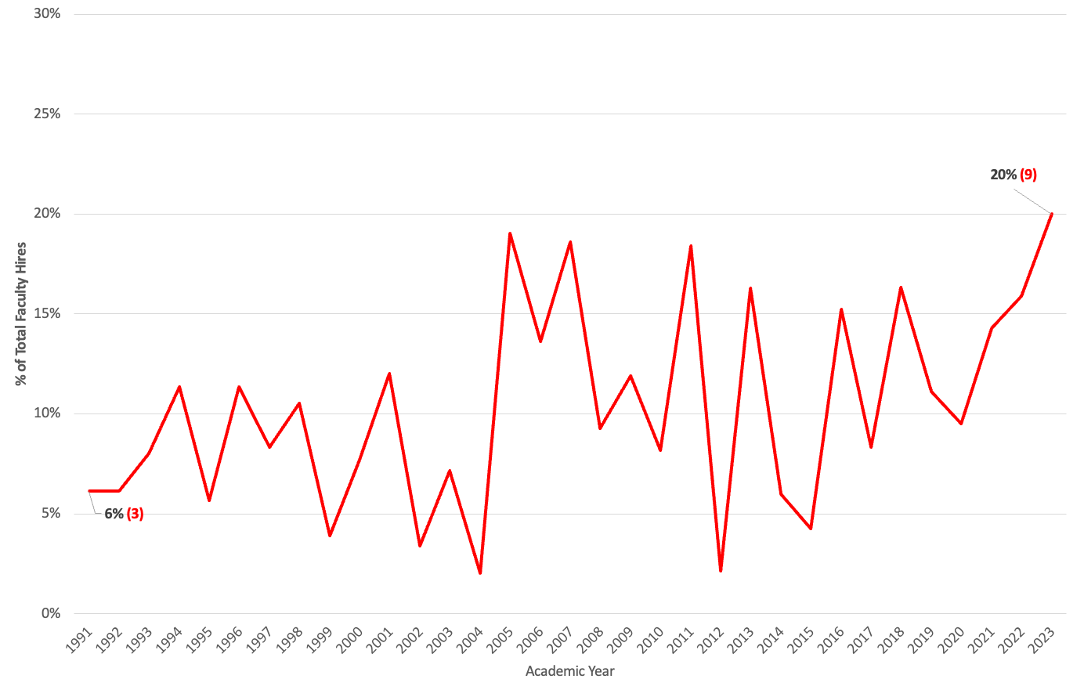

The percentage of newly hired women faculty grew from 14% (N=7) in 1991 to 51% (N=23) in 2023. The percentage of newly hired faculty from underrepresented racial ethnic groups during those years increased from 6% (N=3) to 20% (N=9).

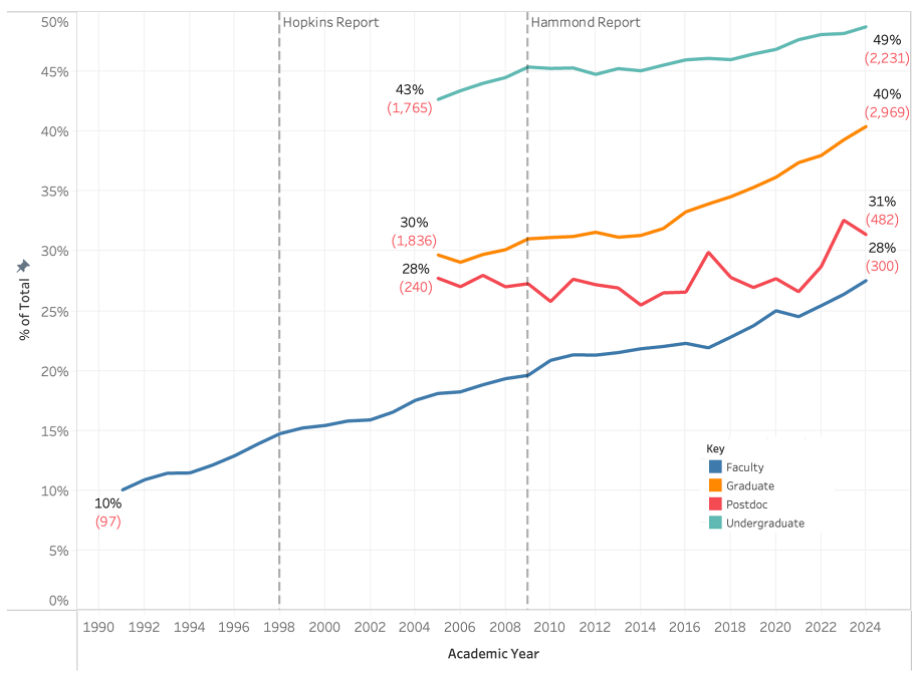

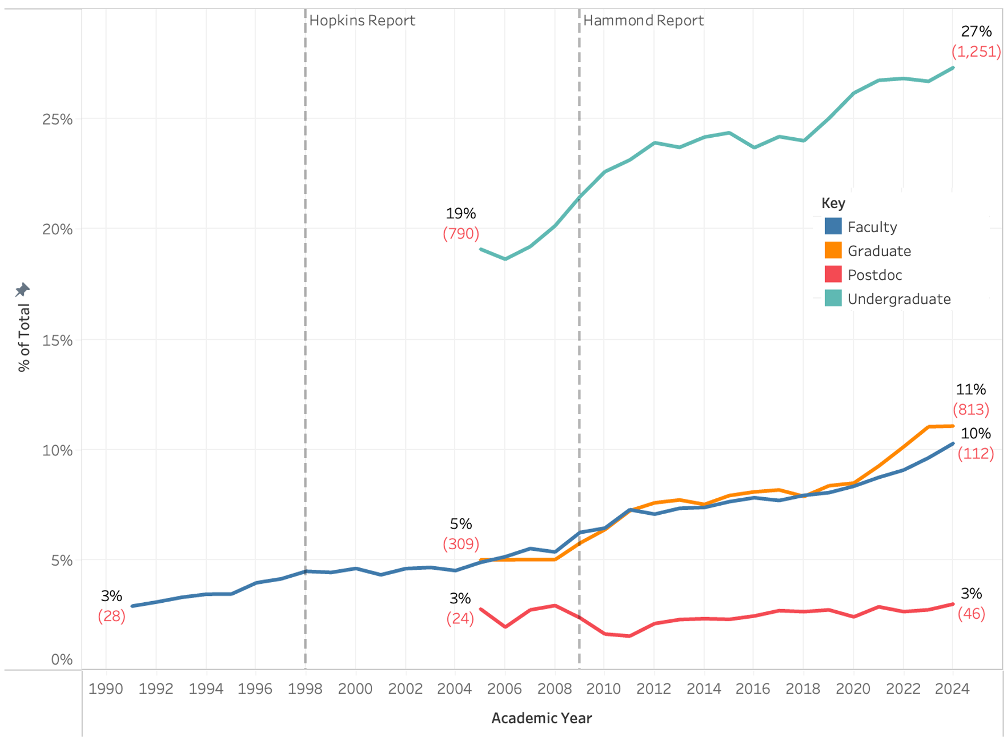

In 1991, women made up 10% (N=97) of MIT’s faculty; faculty from underrepresented groups stood at 3% (N=28). In 2023, 28% (N=300) of our faculty were women and 10% (N=112) were from underrepresented groups.

Percentage of Women Among Faculty Hires by Year (1991-2023)

Percentage of Underrepresented Faculty Among Faculty Hires by Year (1991-2023)

Composition: Women Faculty, Students, Postdoctoral Scholars (1991-2024)

Composition: Underrepresented Faculty, Students, Postdoctoral Scholars (1991-2024)

In short, the updated findings confirm that MIT has fulfilled a 2004 faculty resolution to increase the percent of faculty from underrepresented groups by roughly a factor of two. That said, MIT arrived at the goal a full decade later than the supporters of the resolution had hoped.

The analysis also examined changes in leadership composition. We found that, in 2005, 17% of faculty department heads or lab/center directors were women and 4% were faculty from underrepresented groups. In 2023, those figures stood at 26% and 9% respectively. Among the top leadership positions, such as members of Academic Council, 29% were women in 2005 and 14% were faculty from underrepresented groups. In 2023, those figures were 36% and 18%.

Compensation and space

IR, with the assistance of a faculty advisor, has been conducting a regression analysis of faculty salaries since 2011. Outcomes are reviewed annually by senior academic leaders and the Institute Community and Equity Office (ICEO) to ensure compensation is based solely on performance. Over the past 13 years, the regression analysis has found no statistically significant salary gaps disadvantaging women or faculty from underrepresented groups.

Professor Emerita Hopkins famously used a tape measure to highlight inequitable office and lab space distributions between female and male faculty in the 1999 report. In the summer of 2023, IR examined Institute space data. Their models show that square footage is associated with a faculty member’s number of supervisees and department, lab, or center appointments, research volume, and discipline. Race, ethnicity, and gender were not found to be significant predictors of the amount of space assigned to faculty.

Retention

The 1999 study noted that “the pipeline leaks at every stage of the career” for women in science. As described above, the retention picture for faculty from underrepresented groups in the 2010 report was even more bleak.

To assess changes in faculty retention since the original studies, we conducted a cohort analysis of women and faculty from underrepresented groups, dividing them into three 10-year groups of faculty hired as assistant professors between 1991 and 2020. The results describe three outcomes for each 10-year cohort:

- The number of faculty who remain at assistant or associate professor without tenure (AWOT) status

- The number who received tenure

- The number who left MIT without tenure / before tenure

The bottom line for the earlier two cohorts is that for both women and faculty from underrepresented groups, there are gaps in the tenure rate, with more men and more faculty from non-underrepresented groups receiving tenure. Some members of the recent cohort are still moving along the tenure track so the information is incomplete. At present, 24% of male faculty members in the 2011-2020 cohort have left before receiving tenure compared to 20% of female faculty, and 23% percent of faculty from non-underrepresented groups have departed compared to 24% of their faculty colleagues from underrepresented groups.

Importantly, there isn’t a complete understanding of the reasons faculty choose to leave. Are departures correlated with MIT’s climate and culture? Or are professional opportunities or personal reasons driving faculty decisions?

Faculty experience

Junior women faculty told the authors of the 1999 report that they believed family obligations could affect their careers differently than for their male colleagues. The 2010 report highlighted negative experiences for faculty from underrepresented groups stemming from the sense that some in our community believe “the intentional inclusion or recruitment of a minority faculty member might, in some cases, represent a lowering of standards.” The 2010 report’s authors recommended fostering a culture at MIT that recognizes how diversity advances rather than dilutes excellence.

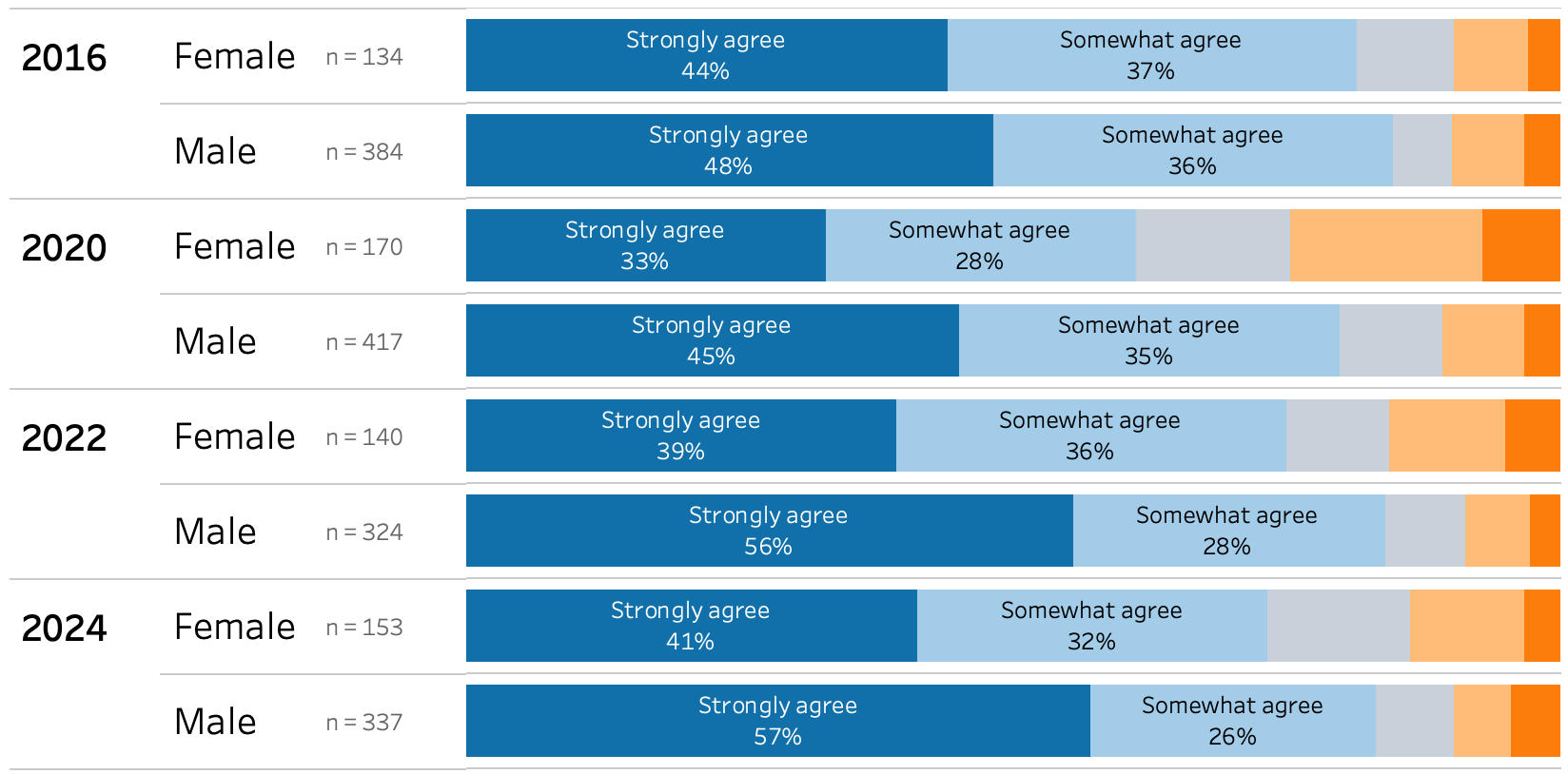

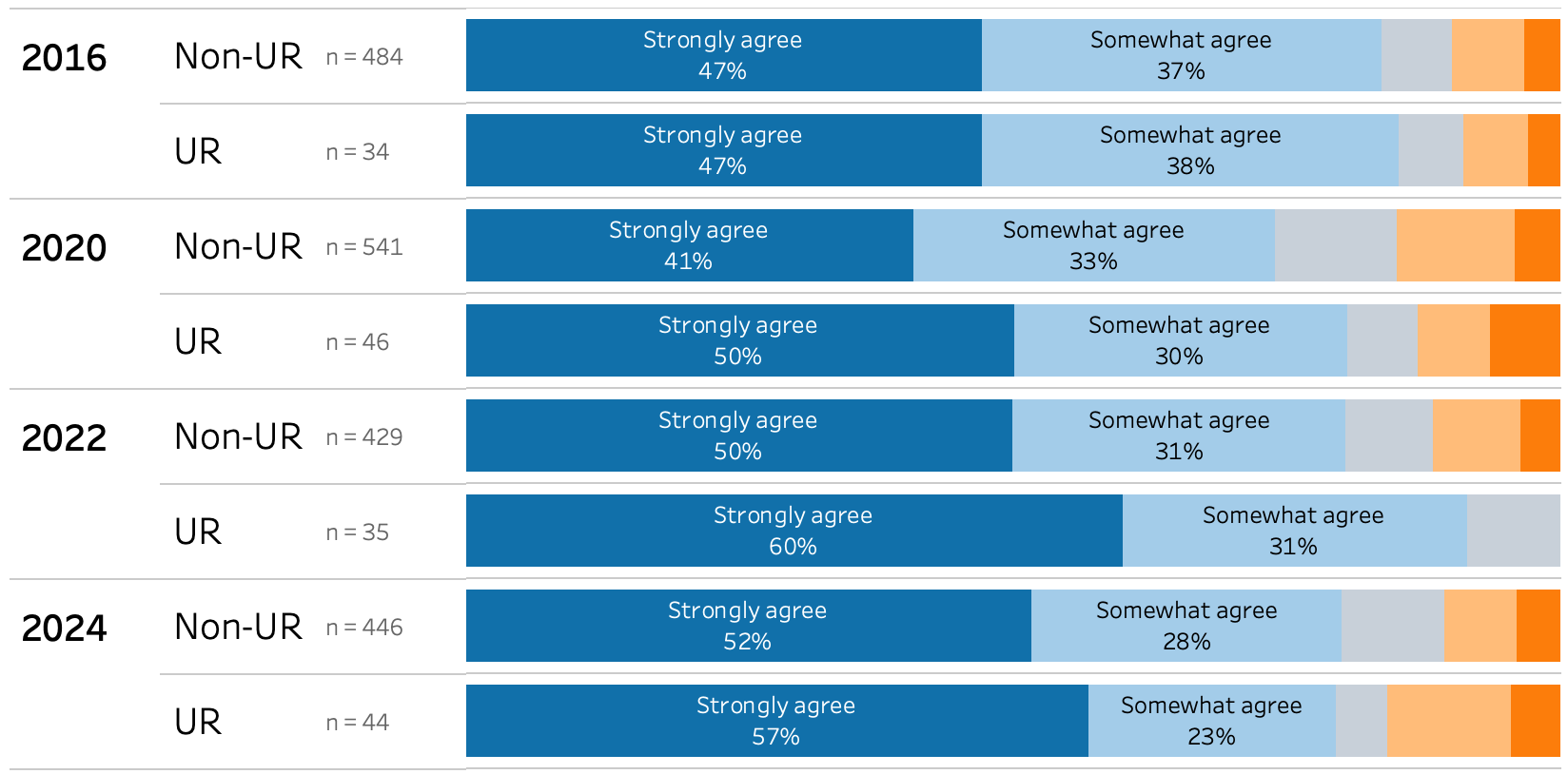

To explore how the MIT experience for women faculty and for faculty from underrepresented groups may have changed in the years since the two reports, the working group examined recent Quality of Life survey results, in particular respondents’ level of agreement with the statement, “At MIT, I am treated with respect.” In 2024, 73% of female faculty respondents strongly or somewhat agreed with that statement compared to 83% of male faculty respondents. Eighty percent of faculty respondents from both underrepresented and non-underrepresented groups agreed with the statement. The Institute needs more clarity about the experiences that informed these responses, specifically for women faculty.

Quality of Life Survey Results: "At MIT, I am treated with respect" (2016-2024)

Partnering on what comes next

With this reassessment in hand, the Institute’s next steps are clearer:

- To maintain the progress of the past several decades, MIT needs to encourage greater adoption of successful recruitment and retention strategies.

- Ongoing monitoring of resource allocation decisions will continue to help to prevent inequities based on race or gender.

- The Institute must close the gaps in its understanding about why some faculty choose to leave MIT as well as why we see differences in quality of work-life experiences.

Responding to findings from the updated analysis

- Throughout the 2024-2025 academic year, Vice Provost Hammond will work with academic deans and department heads to encourage greater adoption of successful recruitment and retention strategies.

- Examples of effective strategies for expansion:

- Junior pre-faculty cohort, postdoc, and visiting scholar programs such as Rising Stars, School of Engineering’s Postdoctoral Fellowship Program for Excellence, and the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Visiting Professors and Scholars Program

- Intentional, targeted outreach during poster sessions, conferences, and campus visits

- Cluster hiring

- Outstanding alumni pipeline

- The Department Support Program will continue to share promising belonging, achievement, and composition practices with departmental leadership.

- Examples of effective strategies for expansion:

- Department Head leadership development programming will focus on how to build a strong department climate, conduct equitable faculty reviews, and effectively manage resources and implement recruitment and retention strategies.

- Ongoing monitoring of resource allocation decisions (e.g., salary, space assignments) will continue to prevent inequities based on race or gender.

- Efforts to learn more about why some faculty choose to leave MIT and why there are differences in quality of work life experiences will advance.

- IR, Human Resources, and Vice Provost Hammond are collaborating on a new exit interview program to explore reasons for faculty departures. The program will determine whether departures are correlated with MIT’s climate and culture or are instead being driven by professional opportunities/personal reasons.

- IR will conduct focus groups to better understand faculty responses to 2024 Quality of Life Survey data about being treated with respect and encountering impediments to doing their best work.